So far what I’ve read, and seen, of

Slavoj Žižek hasn’t really impressed me, but alas, perhaps I have been mistaken. At least so far as the direction an

anonymous reviewer of his latest work,

Organs Without Bodies: on Deleuze and Consequences, I seem agree with him on some points. Of course I won’t go into much detail here, the review is long and dense – so dense I, an undergraduate, am left feeling a little overwhelmed. But I would like to touch on a couple of points that really stood out for me, by offering up some important quotes. I’ll close by lofting a few criticisms that immediately come to mind.

First,

Yet, philosophy and politics constantly risk becoming disassociated in the academy. In Organs, Zizek explains how intellectualism gets "caught up in the academy" through the fetishistic splits performed by academics. A prevailing assumption in the academy across disciplines (from literature studies in the humanities to anthropology in the social sciences to quantum physics in the hard sciences) espouses the "necessary" split between one's "theoretical" academic work and one's life, between one's theory and one's practice. Instead of somehow unleashing our intellectualism, the split produces a spatial gap and a temporal lag that affords capitalism the space-time to further self-revolutionize.

This is a point that those that know me well, know I like to emphasize. It’s generally summarized in brief statements like, “we have to begin by assuming that NOTHING is not normative.” Even if this normativity is negative: via apathy, or passivity – the lines of communication are to omniapparent now for anyone to deny that there is suffering. If you are not trying to do something about it, then you are lame (Of course this does not call for blind action – you might try and figure things out.), and you are onl contributing to its prolongation. The neutrality that so many academics seek is so much the driving force of “late capitalism” (that’s Jameson, and the reviewer does a great job of integrating him into his review). Postmodernism, at least as it is most broadly practiced seems to fall flat on its purportedly emancipatory face. The origins of my distrust lay in two places: firstly, Jameson was the first theorist I ever read; secondly, my own uneasy ascent from poverty into the bourgeois academic establishment. I disliked intellectuals then, and I do now – either you have some goal in mind, and in this respect you are a crusader (for whatever cause), or you are a lifer, and a parasite on society. Why? I can only use this terminology in retrospect, but a crusader has a clear becoming – they are someone, a trajectory for instance, I can speak to.

Also, Zizek will argue in tandem with Lacan,

Only a new and original form of collective social life can overcome the isolation and monadic autonomy of the older bourgeois subjects in such a way that individual consciousness can be lived - and not merely theorized - as an 'effect of structure' (Lacan).

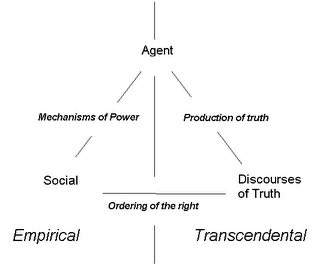

Interestingly I’ve been saying some similar things lately, only I derive my analysis from Foucault. It is rooted in the onto-epistemic triangle I have already outlined in a

previous post. Truth, and this means any critical claim also (whether or not any ‘absolute’ truth is possible by the means of critique), is rooted in man, in society, and in the world; it manifests itself always and everywhere, at any given moment. It cannot, ‘exist’ in itself – it cannot be reified; it can only occur in practice. Practice being the becoming, the presencing, the processing of the process we’ve already described. Practice, because none of this is anything without the active subject. If we wish to alter truth, we can only do so by altering the system, the society, or the body that manifests it. Hence the call for a structural shift – as long as we are not trying to overcome it, we will produce truth conducive to (this epoch of) capitalism. The trouble lies in just how we are meant to overcome this – and apparently our determinism as a part of this system. Zizek seems to think this might be accomplished by returning to some of the tenements of psychoanalysis. He thinks Foucault’s model is great at describing the current situation, but lacks libratory content. The unconscious holds what remains hidden, and hence it is here that we must look to find alternatives. (I think I might look to Spinoza – but this is for another day.)